The following is a short note on recent Portuguese Arbitration Decision (Case 352/2021-T) that decided on February 2022 a case dealing with an internal situation of disproportionate dividends received by a Portuguese corporate shareholder from its qualifying domestic subsidiary leading to the non-application of participation exemption on such dividends.

The Facts

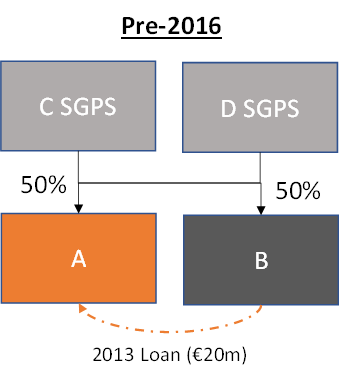

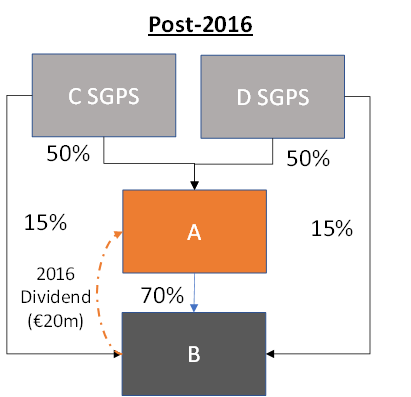

According to the facts of the case, a Portuguese group was controlled by two pure holding companies (Company C and D formed as SGPS) each holding 50% of Company A share capital and these same two holding companies also hold (directly and indirectly) 100% of the share capital of Company B, organized as a limited liability company, also known as Sociedade por Quotas or Lda.

Company B paid upstream dividends in March 2016 and was, at that time, 15% owned by Company C, 15% by Company D and 70% by Company A.

The 70% shareholding of Company A in Company B was acquired on January 2016 through a contribution in kind by the shareholders C and D, which each contributed those shares to Company A share capital. From the background, we also further understand that:

- Company A develops a commercial activity in “hotels, restaurants and tourism and the purchase and sale of properties and resale of those acquired”;

- Company B was subject to bankruptcy proceedings initiated in 2000 and finalized in 2015, when its creditors were fully reimbursed for the amount claimed; and

- Company B provided two loans (in the total amount of €20m) to Company A in 201 used by Company A in the development of its hotel operation activity.

On March 31 2016, the three shareholders of Company B unanimously resolved at a General Meeting to distribute profits in the amount of €20m. In that General Meeting, the shareholders also unanimously declared: “Shareholders C and D would waive receiving any amount related to the Company B profits in the present year, with the company’s profits being fully distributed to Shareholder A, that is, the shareholder agree that the dividends in the amount of €20m will be fully delivered to Company A”.

The corporate structure Pre-2016 and Post-2016 may be depicted as follows:

Company A applied the domestic participation exemption regime (provided in Article 51 of the CIT Code) on the €20m dividends received from Company B, by arguing the fulfilment of the following conditions:

§ Company A held directly and uninterruptedly for 12 months a participation in Company B that is not lower than 10% of the share capital of Company B (the minimum holding period was completed post-distribution);

§ Company B was not tax resident in a backlisted jurisdiction; and

§ Company B was subject to and not exempt from Portuguese corporate income tax and not subject to any tax transparency regime; and

Company A was subject to a tax inspection concluded in 2021 that lead to tax assessment of €1.3m corresponding to 30% of the dividends received. The Portuguese tax authorities argued that the participation exemption rules only exempt an amount corresponding to the precise shareholding held by Company A and as the remaining 30% amount of dividends were due to other entities they would be “other income” in the hands of Company A. Company filled for annulment of the tax assessment with the Portuguese Arbitration Court.

The Decision

The Portuguese tax authorities argued that: (i) entities receiving dividends are exempted only according to the shareholdings held; (ii) participation exemption allows that the qualifying shareholding is held directly or indirectly but not that the distributed profits result from shareholding held by the other shareholders (Company C and D); and (iii) Portuguese Commercial Companies Code specifically provides in Article 22 that “in absence of a special provision or agreement to the contrary, the shareholder shall share in the profits and losses of the company, in the proportion of the par value of their share in the capital”.

Company A argued in return that: (i) the participation exemption rules do not establish any limit, either in absolute value or in percentage value, linking the amount of profits and reserves distributed to a qualifying shareholder; (ii) the rule of Portuguese Commercial Companies Code cited by the tax authorities only applies if “in absence of a special provision or agreement to the contrary” and the General Meeting unanimously decided to establish another criterion; and (iii) the dividend distribution should be valid and only if the tax authorities would have argued that the “main purpose or one of the main purposes” of the dividend resolution was to obtain a tax advantage one could consider that such dividend could be partially recharacterized as other income.

The panel of 3 judges of the Arbitration Court favoured the tax authorities and decided to maintain the tax assessment. The Arbitration Court took a literal interpretation of the participation exemption rules based solely on domestic lawin direct and in conjunction with the rules of the Portuguese Commercial Code. The Court considered that the shareholders only enjoy the right to profits, in proportion to their share in the capital, unless otherwise stipulated in the articles of association of the company. To reach that conclusion the following points were raised:

§ Portuguese tax law “uses as a criterion for the exemption that of the percentage in the shareholding in the company distributing the dividends”. For the Arbitration Court, the elimination of economic double taxation should not apply to the value exceeding the percentage of share capital of Company B arising from a waiver of the right to the profits by the other shareholders.

§ Portuguese corporate law is relevant based on a domestic tax provision that provides that when “undefined terms specific to other branches of law are used in tax law, they must be interpreted in the same sense as the one they have there, unless another derives directly from the law”. In that regard, Portuguese corporate law would require a “contractual amendment” to Company B articles of association establishing a format of distribution of profits different than the percentage of shareholding.

§ The shareholder general meeting resolution does not constitute a distribution of profits, but, at most, an assignment of rights not covered by the dividend exemption rules. The shareholders after waiving their rights to profits proceeded to transfer that amount to Company A as an assignment from Company C and D and, as such, Company A receives an amount not as part of its participation in the share capital of Company B.

Comment

Reading the decision, one immediately wonders if this is not a case of unexpected double taxation on profit distributions which deserves to be discussed.

The core point to be raised is whether the rather domestic law interpretation given by the Portuguese Arbitration Court is correct as regards the term “distributions of profits” and if this should have not been interpreted instead with reference to the EU Parent Subsidiary Directive. One could also raise the hypothetical question for outbound dividends: if Company A would be resident in an EU member State, would Portugal withhold tax on the so-called 30% excess dividends?

First, and despite we are dealing with an internal situation (domestic Portuguese dividends), we should not forget that the applicable tax rules derive from the implementation of the EU Parent Subsidiary Directive. The same concept of “distributions of profits” will also be applicable to situations that are purely domestic in which the national legislator has chosen to use the same solutions as in European law.

On this and along the lines of Terra and Wattel, the term “profit distributions” is an EU law expression that needs to be interpreted autonomously by the Court of Justice of the EU and by the national tax courts in the light of object and purpose of the Directive.

In fact, one should recall that the underlying principle or aim of such Directive, as regards the tax treatment of distributions of profits, was that any profits already charged to corporation tax shall no longer be subject to such tax if they are received by another qualifying shareholder liable for corporation tax. Therefore, only if the concept of distributed profits is given an autonomous EU law meaning (and not a pure domestic meaning) would there be a degree of consistency within the EU as regards its application.

The EU Directive requires that the exemption on profit distributions covered to be linked to a participation of the receiving company in the issued share capital of the distributing company, when it uses the words “by virtue of the parent company’s association with its subsidiary” in Article 4.

But that link existed between Company A (receiving company) and Company B (distributing company). In no moment of the Directive (or its recitals) does the Directive links the exemption to the actual proportion of share capital held or allows withholding tax to be applied if there would be an excess over the profit distributions allocated to a particular shareholding.

Following this line or argumentation, Helminen has also considered that the “EU concept of profit distribution should cover any kind of transfers of benefits from a qualifying corporation to another qualifying corporation for no equivalent value or benefit in exchange, by virtue of the association with the subsidiary”. The term “distribution of profits” should therefore be understood as being broader than the term “dividends” and not applying such approach could subject such profit distribution to potentially unlawful economic double taxation.

It is true that the Court of Justice has yet to interpret the term “distributions of profits” directly, but in the several cases where it dealt with Parent Subsidiary Directive it indicated a strict interpretation of withholding taxes on profits.

In the case at hand, we have a situation of a waiver by two shareholders (Company C and D) of the profits of Company B. Would those shareholders receive the actual dividends, the domestic participation exemption would have applied (as we understand from the background that Company C and D would qualify for the exemption).

This is perhaps the strangest part of the outcome of the decision, because the waiver by those shareholders did indeed originate an economic shift towards Company A but that shift is no more than a disguised contribution to the capital of Company A (of profits already taxed). The Court seems to address this point when asserting that “at most, [we are dealing with] an assignment of rights not covered by the dividend exemption”. But, also let’s not forget that taxing the so-called “excess profits” would be equivalent to taxing the hidden capital contribution.

One could even argue that the top shareholders likely wanted to distribute the profits to Company A for this company to have sufficient funds to close the open financing it had with Company B. Nothing is mentioned on the case facts, but one wonders if the willingness to have saved a legal step (i.e. distributing profits to Company C and D and later fund Company A with those proceeds) has not cost dearly in economic double taxation.

On that point, there is extensive doctrine on whether the Parent Subsidiary Directive is applicable in situations regarding covert or disguised distributions. To the extent that there is a parent-sub relationship and is not a situation of abuse, why would the profits distributed in excess fall out of the scope of the Directive?

We would have better understood the arguments of the Arbitration Court, if we would be dealing with an arrangement leading to a waiver of a dividend entitlement by a shareholder that would have itself not qualified for exemption (e.g. if it would have been individual shareholder).

This is also relevant because Portugal transposed (since early March 2016) the Parent Subsidiary Directive GAAR into the participation exemption regime for both inbound and outbound dividends. Under such GAAR, the dividend exemption would not be applicable in the case of an arrangement put in place for the main purpose, or having as one of its main purposes, the obtaining a tax advantage that frustrates the goal of avoiding double taxation and is not genuine (i.e. without valid commercial reasons that reflect economic reality).

The line of argumentation based on potential abuse was not raised by the Portuguese tax authorities and therefore the Arbitration Court identification of “literal interpretation” limiting profit distributions to the percentage of share capital seems to be entirely based on a reference back to Portuguese commercial law concepts, rather than pursuing an autonomous EU law interpretation routed on the need to eliminate the economic double taxation.

So, why did not the Arbitration Court raise the EU Law angle?

Likely because Company A did not raise the EU law card. Perhaps if it had used Case C‑48/07, which held “with regard to Community law, the Court may not diverge, within the limits of the reference of domestic law back to Community law, from the interpretation provided by the Court” (Paragraph 27, in fine), we could have had a preliminary reference to the Court of Justice of the EU and possibly a different outcome.

26/04/2022

Tiago Cassiano Neves